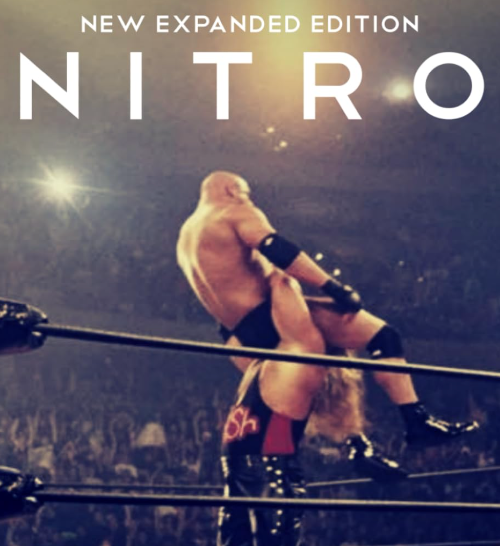

Reviewing Guy Evans' Nitro

Wrestling fans of a certain age will focus on the Monday Night Wars as a crucial period in wrestling history, when there was a genuine competition between two well-funded competitors and WWF ("The Fed") genuinely seemed to be on the brink of bankruptcy.

I just started reading Guy Evan’s Nitro. I’m about a third of the way done, but can already say that this book is already a huge improvement over Death of WCW. I had inadvertently read Death of WCW last year thinking it was the source of the VICE documentary, Who Killed WCW?. (I have no idea how this book somehow has 4.7 stars based on 310 ratings. Did y’all read the book?) The Nitro book is way, way better of the two. This week, I’ll be live-blogging the best tidbits from book and posting highlights from Guys Evan's Nitro.

Eric Bischoff as Protagonist

Wrestling fans of a certain age will focus on the Monday Night Wars as a crucial period in wrestling history, when there was a genuine competition between two well-funded competitors and WWF ("The Fed") genuinely seemed to be on the brink of bankruptcy. The author Guy Evans is largely sympathetic to Eric Bischoff as an innovator in the wrestling industry and the catalyst for the Monday Night Wars. Kevin Sullivan also gets more credit as the head booker, a role that I was unaware of before reading the book. Nitro does a fantastic job of explaining the corporate environment at Turner Broadcasting Station that Bischoff had to operate in and even has a compelling character sketch of Ted Turner, "Billionaire Ted."

“Sports such as baseball and football have continued to show profits only because of TV. It is that thin a line, and TV has let them stay in the black and justify ridiculous players salaries. Pull TV out materially, and the whole structure could collapse.”

WCW was a TV company and WWF was a wrestling company. This distorted incentives greatly, since WCW was constantly trying to maximize for weekly ratings. “WCW is a television company doing wrestling…while WWF is a wrestling company doing wrestling.” This book goes into much, much more detail about what that corporate hierarchy within the Turner Empire was actually like and how this helped and hindered Bischoff. Readers who have worked in large corporations will be impressed by how Bischoff is able to make a career for himself against a corporate environment that was very anti-wrestling. Before Bischoff makes big moves to get WCW on equal footing with WWF, he's a WCW announcer and largely a cog in a large corporate machine.

“Dubya Cee Duyba”

One of Bischoff's biggest victories was to get advertising buyers to take wrestling seriously. Part of this was regional bias against a Southern property. “Dubya Cee Duyba” had a down market feel. As a Southern fan who used to watch “Dubya Cee Duyba” before the Monday Night Wars, I can confirm that WCW indeed had a more rasslin’ feel. That’s what I liked about it. Dubya Cee Duyba rasslin’ had its charms: although the production values and lighting were worse, there were fewer cartoonish characters and the matches felt more like a shoot. WCW still struggled to win over advertisers though:

“...advertisers couldn’t get their head around the fact that wealthy people were watching WCW. “In fact, this one sales guy wanted to do a sales tape where would film the cars at a WCW event…with the Range Rovers, the Mercedes, [and son[. His point was, ‘this looks like an NFL parking lot’, and the NFL gets the highest CPM’s (cost person thousand impressions) on television.”

"They could not get advertisers over the hump this was not a ‘downscale’ [property]. So it didn’t drive ad sales rates.”

Once Nitro becomes a big hit and the Monday Night Wars take off, Bischoff has armed the ad sales team with real talking points:

“It touted Nitro as an undoubted ratings winner, attracting ‘more teens than MTV’, ‘more men than ESPN’ and an average of 1.2 million viewers in the coveted 18-49 male demographic.”

WCW: Before & After

“WCW was nothing but a bunch of guys pushing their sons. If you didn’t have a dad in the business, you couldn’t even get an opportunity.”

Nitro largely takes the contract negotiations from the corporate view. Before the Monday Night Wars, large majority of WCW wrestlers worked under guaranteed contracts. Ted Turner also owned the Atlanta Braves, so “...viewing WCW contracts as analogous to those used in ‘real’ sports enabled a consistency of operations within Turner Sports.” Marcus "Buff" Bagwell describes making $150,000 a year but having to beg people to come in off the streets to watch their shows. "We had to beg people to come in to watch free wrestling." Before the Monday Night Wars, the ethos of WCW was: "Just keep your head down, stay out of trouble, and you'll have a job for life."